By: Eleena Ghosh

Happy America Recycles Day! We’re all familiar with the black, green, and blue bins that are spread across campus today but once upon a time (the 1960s), this campus didn’t recycle or compost. It was thanks to the activism of students in the Environmental Conservation Organization (ECO) and Maryland Public Interest Research Group (MaryPIRG) that administrators even began to think about it. Today, only MaryPIRG remains, but they’re still doing great environmental work.

Early history:

- May 1969, a “Trash Bash” was held on campus, where 500+ students participated in a weeklong campus clean-up that was organized by Greek Week committees and the North American Habitat Preservation Society. There were also student and administration speakers, along with a “jug band and folk group” to soundtrack their clean-up.

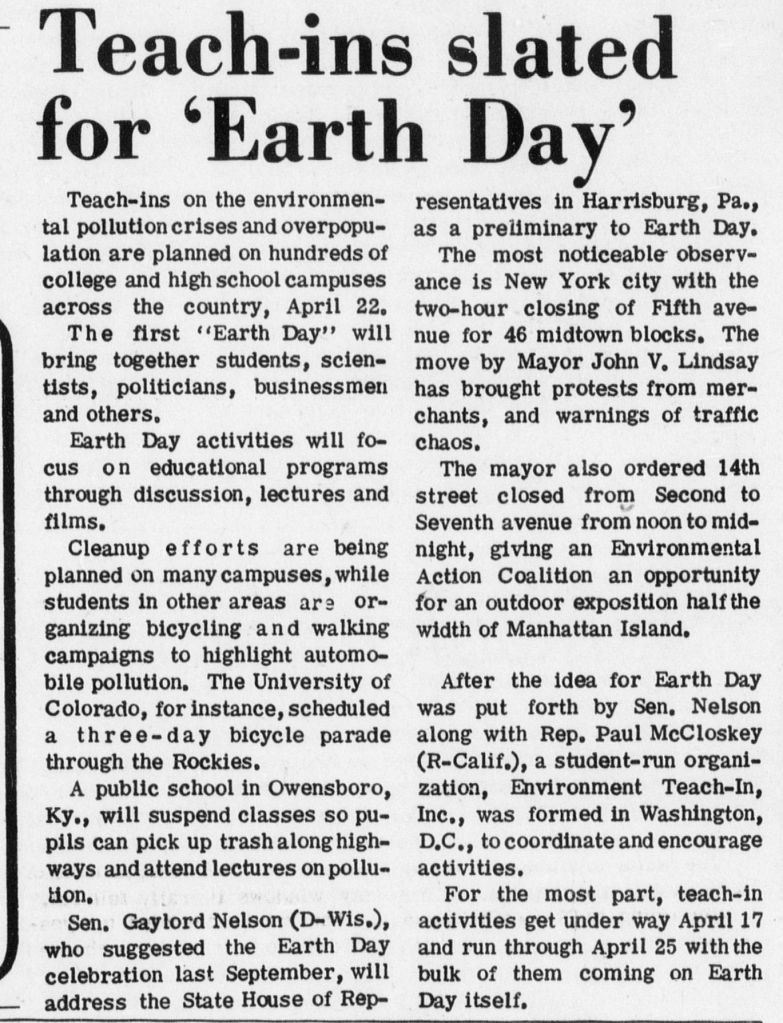

- April 1970, the campus and the nation celebrated the very first Earth Day! There were day-long teach-ins, films, displays, and speeches.

- March 1971, student-led ECO, which organized around issues of recycling, toxic runoff, and pollution, successfully proposes and pushes for the university’s first campus recycling center; run entirely by student volunteers, the UMD recycling center predates that of PG County.

The Diamondback, November 5, 1971

- November 1972, Political activist/reformer Ralph Nader speaks on campus, which leads to the creation of another student organization, the Maryland chapter of the Nader-backed Public Interest Research Group (MaryPIRG).

ECO did much of the early work that began this university’s journey towards recycling, composting, and waste reduction. Throughout the 70s and 80s, ECO volunteers (read: students) would collect paper, cardboard, and aluminum waste from bins in the dorms, offices, businesses, and take them to a nearby recycling center in the ECO truck. Eventually, in 1971, they succeeded in establishing a recycling center directly on campus, which they largely ran themselves.

Truck — Environmental Conservation Organization, n.d., Diamondback Photos, Box 87, Item 8953

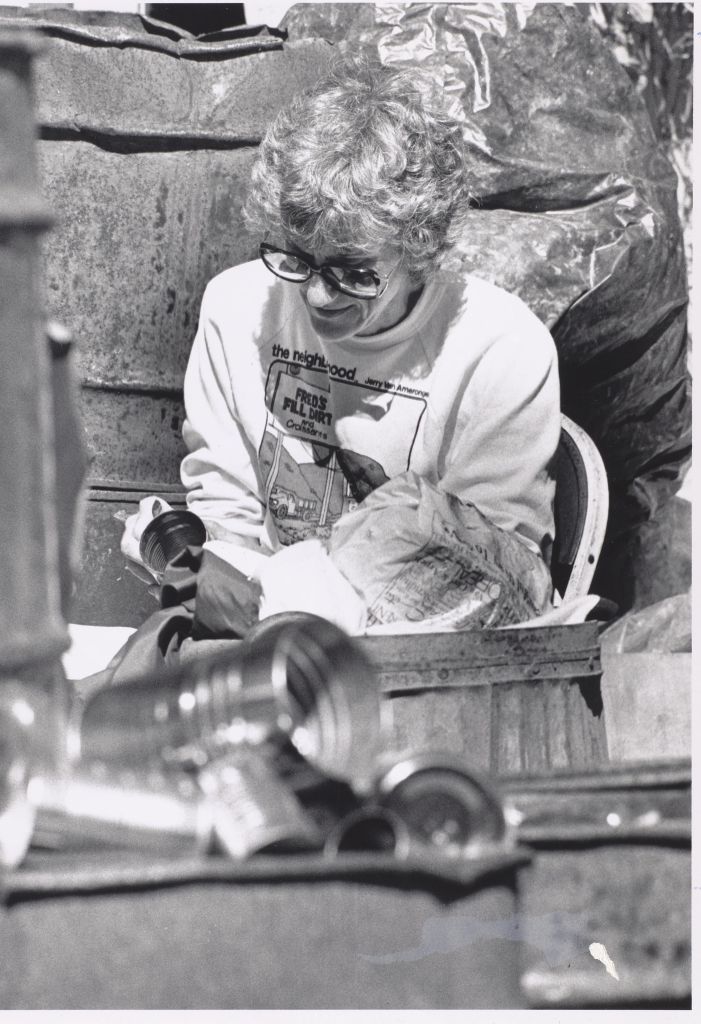

Mary Ann Harrison, ECO Volunteer, removes paper wrappers from tin cans, 1975, Diamondback Photos, Box 127, item 13588

The center had to be consistently fought for, as university officials and administrators consistently threatened its existence; for example, in 1976, the space was eyed to create a parking lot for shuttle buses. Because the university never gave the center any funding, it eventually began to struggle to stay open and operating, because of student turnover. Though this begs some more digging, the recycling center likely became Facilities Management.

The Diamondback, April 2, 1976

Along with ECO, MaryPIRG became the two most active student groups when it came to recycling and waste management on campus. One of their longest-lasting and more ambitious (and, most successful!) projects was targeting dining hall waste, particularly styrofoam waste.

Though the movement towards recycling more and waste consciousness had existed long before, even among students, the story with the dining halls really began in 1991, when they switched from paper products to Styrofoam (polystyrene). Almost immediately, MaryPIRG was vocal in their criticism of that choice, first suggesting that food services completely eliminate carryout altogether. Barring the increased litter and pollution that comes from Styrofoam use, MaryPIRG based their campaign on the argument that polystyrene is also harmful to the user’s health and acts as a carcinogen (so said Sharon Williams, campus coordinator for MaryPIRG) and argued that it should be completely phased out– a position they made clear with their “Phase Out Foam” day. A chemistry professor did, however, publicly assert that those statements were “completely untrue” in the Diamondback.

Though Food Services Assistant Director Joseph Mullineaux decided not to completely ban Styrofoam products, he did announce that the dining halls would begin recycling carryout containers in the Spring of 1992.

Student opinions varied on the subject, but generally, it seems that they were on board with MaryPIRG’s original campaign to completely phase styrofoam out. The Diamondback ran a few opinion columns and Letters to the Editor from students that affirmed that position- or at the very least supported the recycling of styrofoam.

As part of what eventually became the “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle Campaign”, MaryPIRG continued to hold events around campus in the hope to educate students about waste, excess packaging, and styrofoam. In September of 1992, they gave out “Wastemaker Awards” outside Stamp Student Union to companies like Kool-Aid and Chef Boyardee hoping to open people’s eyes about the excessive packaging that came with many products.

The Diamondback, October 22, 1992

After a small dip in activity, MaryPIRG and ECO’s efforts picked up again in 1994, when campus stopped recycling styrofoam after the Dining Services’ contract ended with Eastern Waste. The two groups immediately began to promote alternatives to styrofoam, like number one and two plastics, paper products, and reusable mugs, and even met with Mullineaux again to advocate for the use of these materials. Although it seemed he was interested, there was no move to implement the ideas. As a result, MaryPIRG and ECO took it upon themselves to begin the work on implementing reusable mugs in dining halls and continuing to educate students about waste.

And educate they did. There were numerous tables held around campus, but perhaps the most notable was the one outside of Stamp Student Union in the fall of 1994. Accompanying informational flyers and pamphlets was an eight-foot dinosaur made out of trash and wire on display. Hey, nobody can ever say environmentalists were boring.

Hoffman, Chris., Dinosaur made from trash on display at MaryPIRG event in front of Stamp Student Union, 1994, Diamondback Photos, Box 42, Item 4050.

MaryPIRG’s main focus was on convincing students to use reusable mugs rather than the styrofoam carryout mugs that were offered to them at the dining halls. Finally, after two years of on-the-ground organizing and meetings with campus officials, the campaign was officially accepted and implemented by Dining Services. Students could buy reusable mugs at dining halls and campus convenience stores for $2.25 and then receive a discount at dining halls whenever they used them. The campaign was slow going at first but picked up with kitschy flyers that prompted students to “go get mugged” at the dining halls.

The Diamondback, March 27, 1996

But that didn’t mean their work was over. Even as their reusable mugs were being implemented, they began looking towards their next project to replace the dining halls’ Styrofoam carryout containers with recyclable plastics. Though that took many years, the students of MaryPIRG never gave up– even in 1998, they were very vocal about their criticism of the university’s continued use of Styrofoam containers. It wasn’t until 2007 that we saw the university switch to the compostable packaging and containers that we know and love today.1

The Diamondback, April 22, 1998

Today, UMD keeps 58% of its waste out of landfills through composting and recycling (as of 2022)2 and was ranked #1 out of the Big 10 and Maryland institutions in the Campus Race to Zero Waste competition.3 Wherever there’s a trash can, there’s sure to be recycling and composting bins right next to it.

As many of the great things about this university are, it’s all thanks to the activism of the early students.

Works Cited

- “Composting.” (n.d.) Facilities Management. https://facilities.umd.edu/services/recycling-waste-management/composting

- “Composting.” n.d. Facilities Management. https://facilities.umd.edu/services/recycling-waste-management/composting

- Small, A. (January 21, 2021). UMD’s Journey to Curbing Waste. https://sustainingprogress.umd.edu/celebrating-stories/umds-journey-curbing-waste

Eleena Ghosh is a graduate student assistant in University Archives, pursuing a Master’s of Library and Information Sciences and a Museum Scholarship and Material Culture Certificate. She is interested in museum studies, creating more inclusive archival records and spaces, anthropology, and figuring out how to combine all of her different interests.

As someone who works with and creates maps, I know maps can tell various stories. As the saying goes, “A picture is worth a thousand words.” Maps can do the same, especially looking at maps of the same location from different decades. In this project, I looked at old campus maps starting from when the University of Maryland (UMD) was Maryland Agricultural College (MAC) to tell the story of how the campus changed since its charter in 1856.

As someone who works with and creates maps, I know maps can tell various stories. As the saying goes, “A picture is worth a thousand words.” Maps can do the same, especially looking at maps of the same location from different decades. In this project, I looked at old campus maps starting from when the University of Maryland (UMD) was Maryland Agricultural College (MAC) to tell the story of how the campus changed since its charter in 1856.

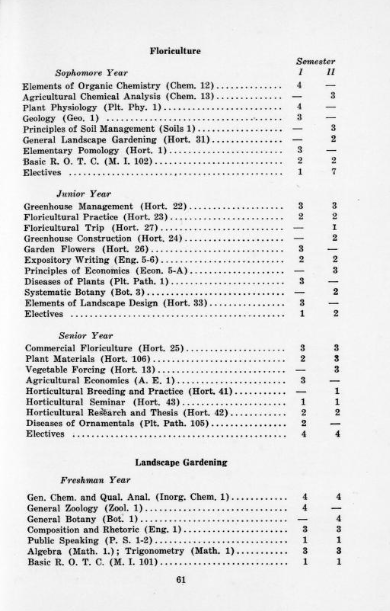

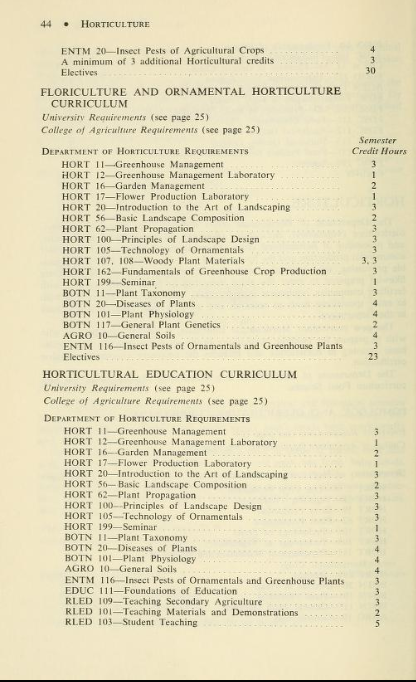

Students in the Horticulture Department in 1928 took a variety of classes including “Public Speaking,” “Greenhouse Construction,” and “Vegetable Forcing.”

Students in the Horticulture Department in 1928 took a variety of classes including “Public Speaking,” “Greenhouse Construction,” and “Vegetable Forcing.” Curriculum in 1968 bears strong similarities to the coursework of 1928. However, focus has shifted to lab work and technology. Courses like “Flower Production Laboratory” and “Technology of Ornamentals” indicate the growing role of technology in science following World War II.

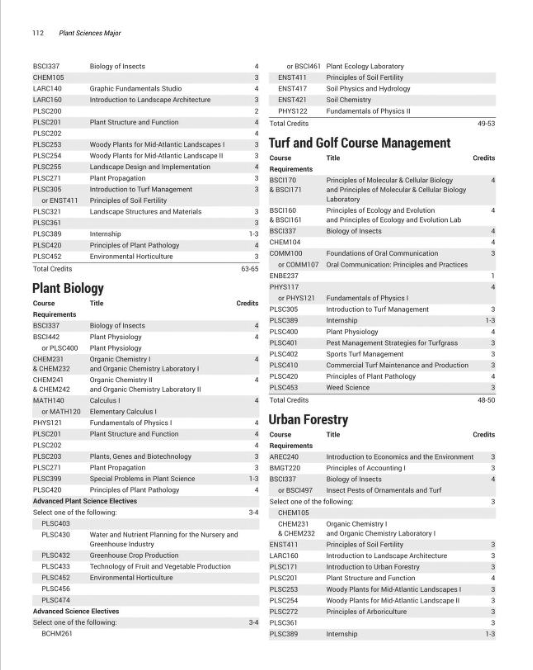

Curriculum in 1968 bears strong similarities to the coursework of 1928. However, focus has shifted to lab work and technology. Courses like “Flower Production Laboratory” and “Technology of Ornamentals” indicate the growing role of technology in science following World War II. Current courses in the Department of Plant Sciences show more science courses and laboratory work.

Current courses in the Department of Plant Sciences show more science courses and laboratory work.