By: Eleena Ghosh

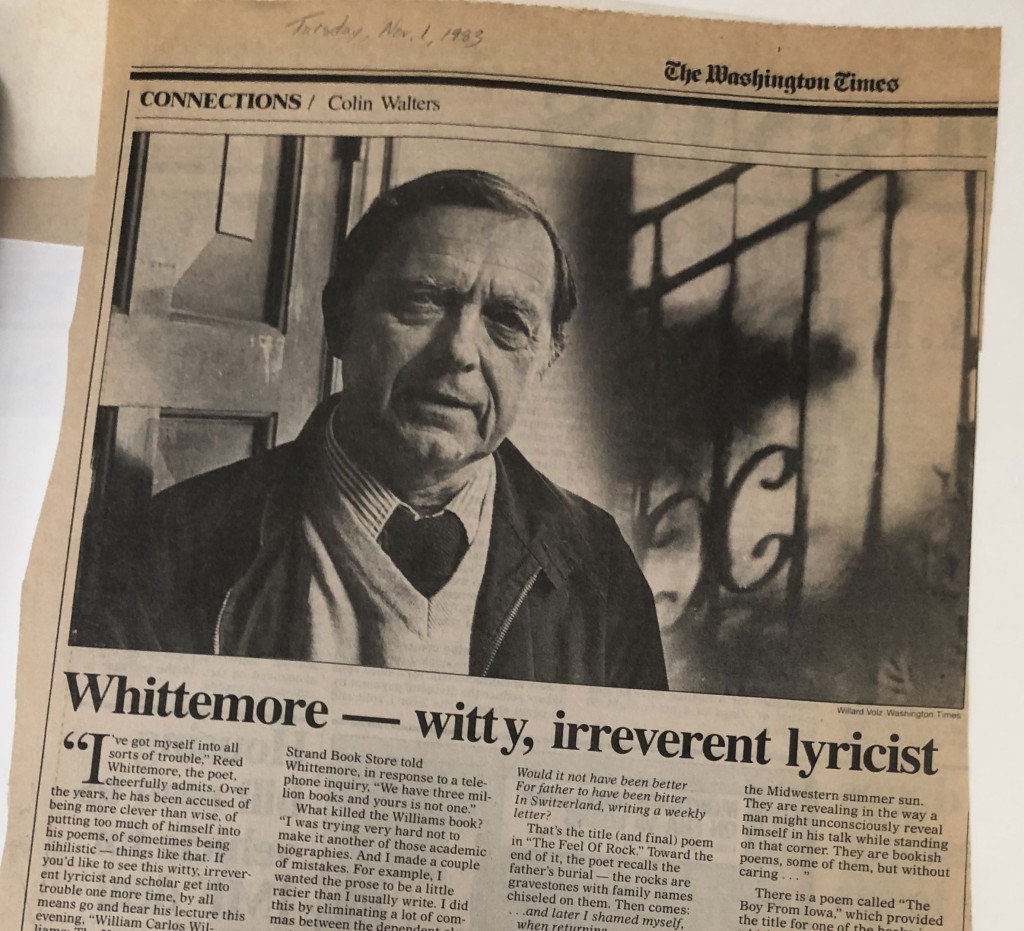

April is National Poetry Month and to celebrate, we’re spotlighting a collection that will speak to poetry fans everywhere: the Reed Whittemore papers.

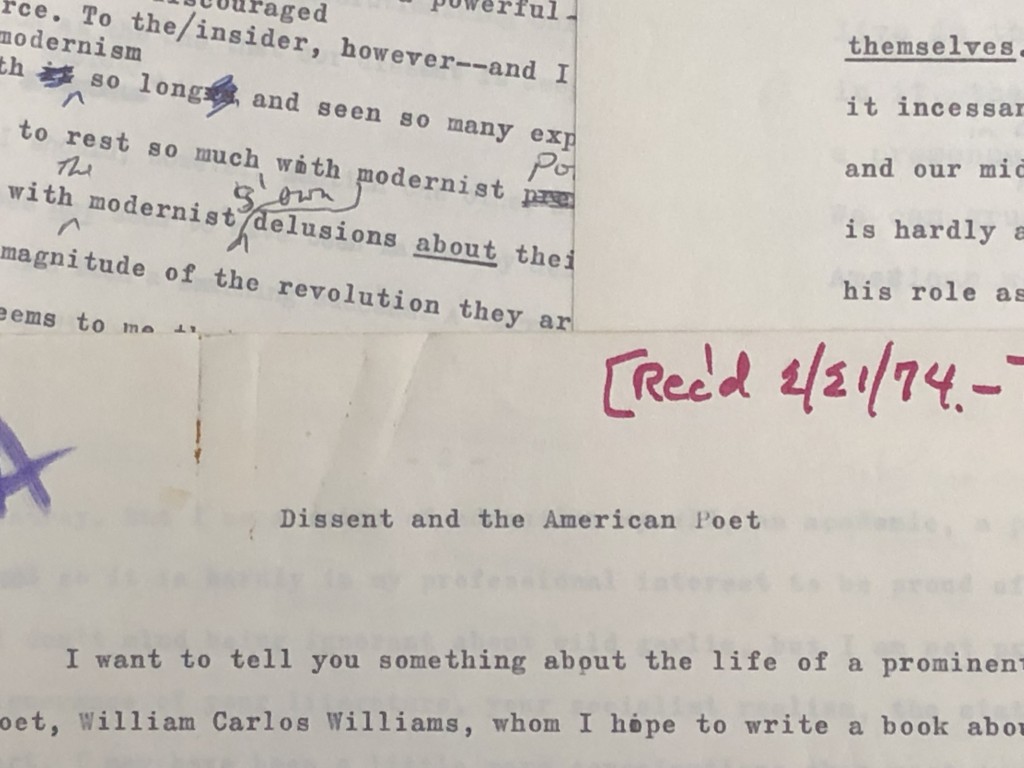

Whittemore was a professor of English here at the University of Maryland, College Park from 1966 to 1984 (almost 20 years!), and also a poet, essayist, and literary critic. He authored nearly a dozen poetry collections, as well as nine other works of criticism & biography, not to mention his work as editor of numerous literary magazines. The extensive collection of his papers contains personal correspondence, manuscripts, lecture notes, published works, & photographs.

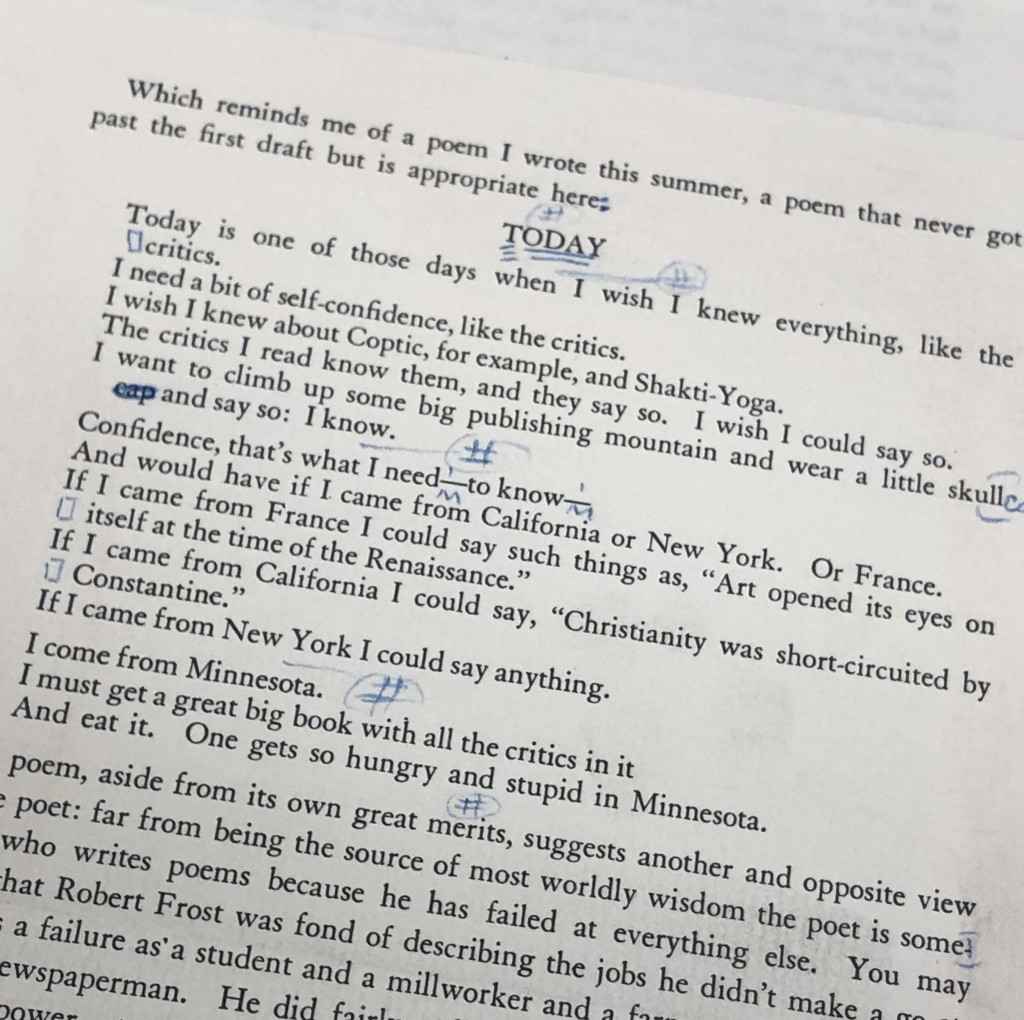

Whittemore’s legacy as a remarkable poet lies in the sincerity and earnestness in which he moved through life; nothing was too small or insignificant for his attention and appreciation. On the whole, his poetry is a subversion of what one comes to expect of the genre– it is humorous and unsubtle in its satire and irony, perhaps even silly at times. More often than not, he wrote about things generally considered unpoetic or prosaic. In 1974, his interviewer at the Washington Post titled him “a poet of his culture, with godlets as worthy of his attention as sunsets were of Wordsworth’s… [explaining] much of the richness in Whittemore’s poetry– his generosity in giving himself to the subject that other poets might ignore as unpoetic.”1

But don’t be fooled– it wasn’t uncommon for Whittemore to explore things like capitalism and bureaucracy, heroism, or questions of identity in his writing too. But what made him so exceptional was his trademark style, a playful humor belying a deep subversion below. It’s here we can clearly see the multitudes in his writing– there is amusement, yes, but anger, melancholy, and tenderness too.

His writing packed a punch, but one you usually never saw coming. Like Whittemore himself, his writing is “clear-eyed, accessible, complicatedly optimistic, and fierce.” 2

We’re lucky to not only have a comprehensive collection of his works, but also his teaching material; after all, who better to learn poetry from than a former U.S. Poet Laureate? His class schedules, syllabi, and notes offer a peek into what his classes must have looked like and what advice he had for young poets, as well as some unpublished material he used as examples in class.

To many poetry lovers, Whittemore’s poetry brought back into focus what poetry is truly for. It gives a voice to the feelings and actions that we can only describe in metaphors or stories or prose; those things need not always be profound, palatial things, but that doesn’t mean they don’t take up space in our heads and hearts. Sometimes, it’s being from Minnesota and other times, it’s the idea of dissent in our everyday lives. Either way, big or small, these feelings and ideas are part of the human experience and, as such, will themselves to be written down, dissected, re-written, and, ultimately, shared. Whittemore’s willingness to equally share the beauty and humor in life with the melancholy and misery made his work that much truer to the human condition and that much more appealing.

1 McCarthy, C. Nov 8th, 1974. A poet of the sidelines. The Washington Post.

2 Koen, B. April 11, 2012. Reed Whittemore: An Appreciation. Library of Congress. https://blogs.loc.gov/catbird/2012/04/reed-whittemore-an-appreciation/

Eleena Ghosh is a graduate student assistant in University Archives, pursuing a Master’s of Library and Information Sciences and a Museum Scholarship and Material Culture Certificate. She is interested in museum studies, creating more inclusive archival records and spaces, anthropology, and figuring out how to combine all of her different interests.

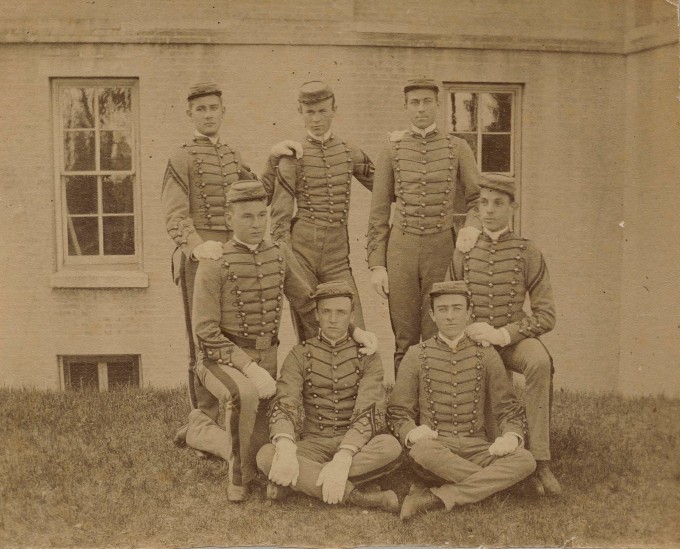

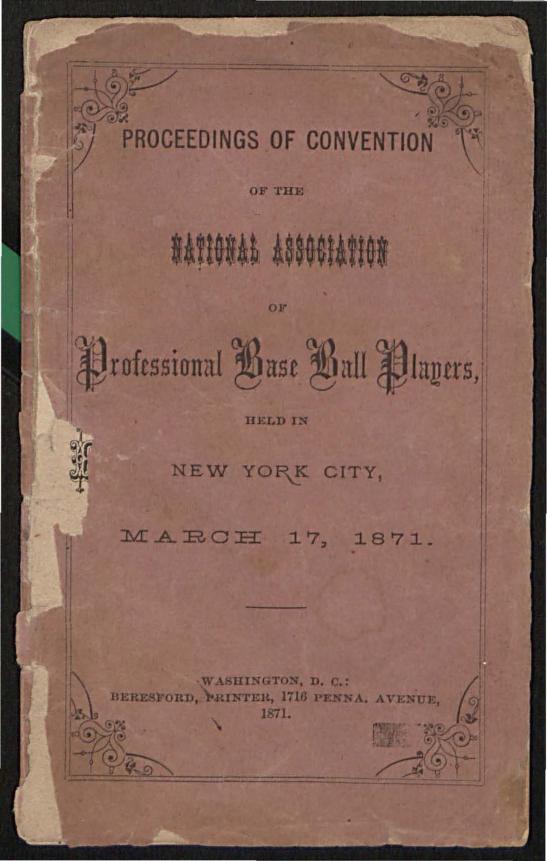

Another early indication of the presence of baseball on the M.A.C. campus is the grouping of baseball rule books, dating from 1871 to 1910, found in the mid-1990s among the records of the University of Maryland President’s Office. Although there is no direct proof that these rule books were used at M.A.C., their presence among the president’s files would seem to imply that the cadets were indeed playing baseball at that time.

Another early indication of the presence of baseball on the M.A.C. campus is the grouping of baseball rule books, dating from 1871 to 1910, found in the mid-1990s among the records of the University of Maryland President’s Office. Although there is no direct proof that these rule books were used at M.A.C., their presence among the president’s files would seem to imply that the cadets were indeed playing baseball at that time.

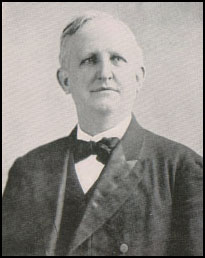

The first Terp to play baseball professionally was Simon Nicholls (Class of 1903), who played shortstop for the Detroit Tigers, Philadelphia Athletics, and Cleveland Naps in the early 1900s.

The first Terp to play baseball professionally was Simon Nicholls (Class of 1903), who played shortstop for the Detroit Tigers, Philadelphia Athletics, and Cleveland Naps in the early 1900s.

individuals have had time to reflect on what 9/11 means to them and how it affected both their communities and their relationship to our country. University Archives would like to take time today, on this solemn anniversary, to reflect on the impact of the terror attacks on the University of Maryland and its surrounding communities.

individuals have had time to reflect on what 9/11 means to them and how it affected both their communities and their relationship to our country. University Archives would like to take time today, on this solemn anniversary, to reflect on the impact of the terror attacks on the University of Maryland and its surrounding communities.

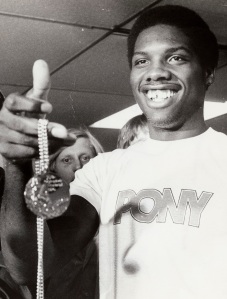

As a tremendous, aggressive defensive star, Victoria “Vicky” Bullett was the youngest member (age 20) of the U.S women’s basketball team at the 1988 Summer Olympic Games in Seoul, South Korea. Vicky scored four points to help Team USA defeat Yugoslavia (77-70) for the gold medal! On her return from South Korea, Vicky stated that, “I’m in a daze, it still hasn’t really hit me yet. It was a great experience, very exciting.”¹ Vicky Bullett graduated from Maryland in 1989 with a degree in General Studies.

As a tremendous, aggressive defensive star, Victoria “Vicky” Bullett was the youngest member (age 20) of the U.S women’s basketball team at the 1988 Summer Olympic Games in Seoul, South Korea. Vicky scored four points to help Team USA defeat Yugoslavia (77-70) for the gold medal! On her return from South Korea, Vicky stated that, “I’m in a daze, it still hasn’t really hit me yet. It was a great experience, very exciting.”¹ Vicky Bullett graduated from Maryland in 1989 with a degree in General Studies.

At the young age of six, Dominique Dawes began a long and successful career as a gymnast. Twelve years later after numerous competitions and already an Olympic veteran (competing in the 1992 Olympics), she once again proved her ability by gaining a position on the U.S. women’s gymnastics team for the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. By the end of the games, the team earned the nickname “Magnificent Seven” and became the first U.S. women’s gymnastics team in Olympic history to win a gold medal. Dawes would later graduate from University of Maryland (though never a member of UMD Gymnastics) in 2002 and is currently a co-chair of the President’s Council on Fitness, Sports and Nutrition while working for Yahoo Weekend News.²

At the young age of six, Dominique Dawes began a long and successful career as a gymnast. Twelve years later after numerous competitions and already an Olympic veteran (competing in the 1992 Olympics), she once again proved her ability by gaining a position on the U.S. women’s gymnastics team for the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. By the end of the games, the team earned the nickname “Magnificent Seven” and became the first U.S. women’s gymnastics team in Olympic history to win a gold medal. Dawes would later graduate from University of Maryland (though never a member of UMD Gymnastics) in 2002 and is currently a co-chair of the President’s Council on Fitness, Sports and Nutrition while working for Yahoo Weekend News.²