By: Eleena Ghosh

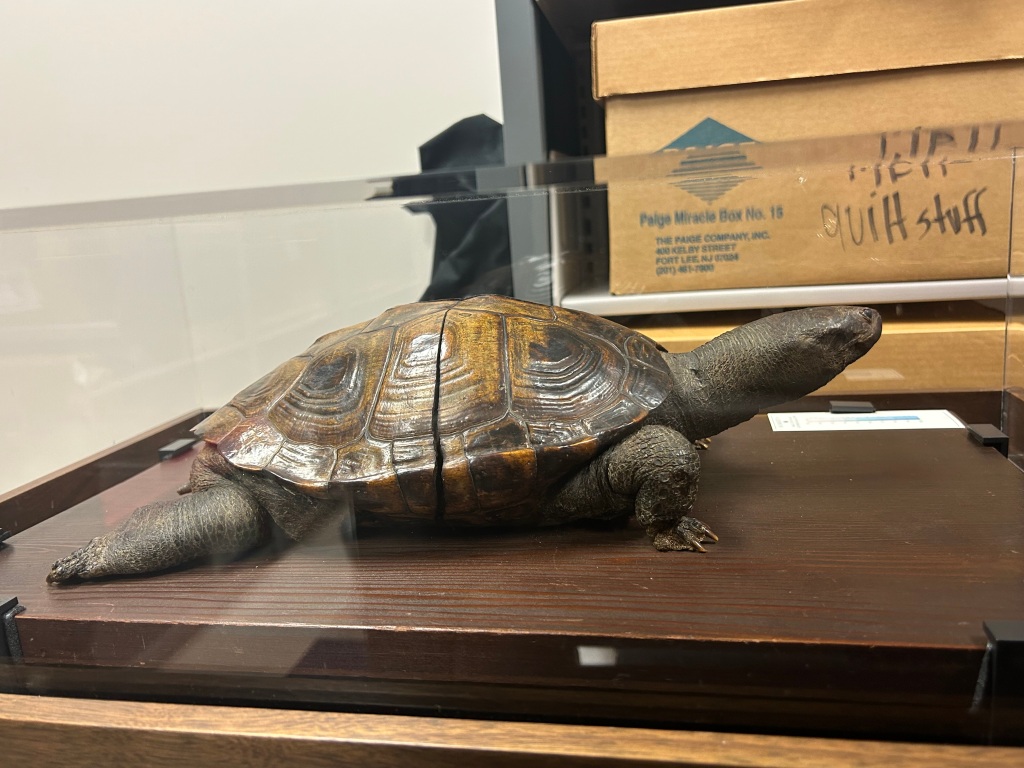

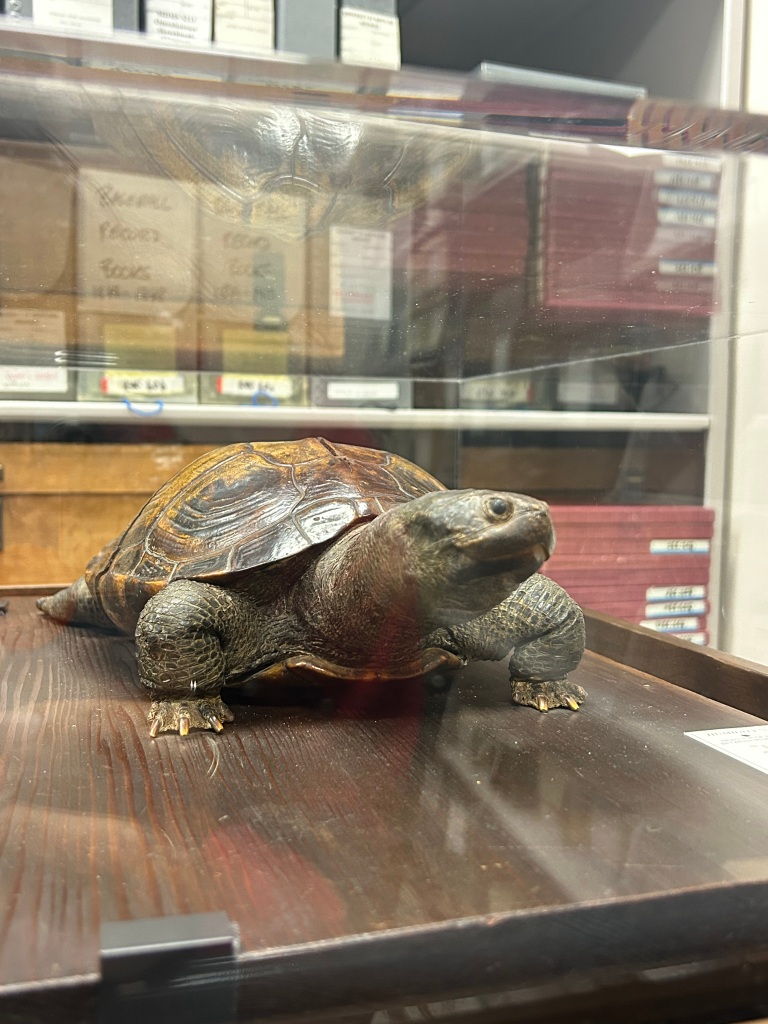

Original Testudo, taxidermized, Memorabilia Collection no. 171, University Archives, University of Maryland, College Park

We missed National Trivia Day earlier this month, but we’ve still got some fun UMD trivia for you! Did you know that our beloved Testudo is actually a woman?

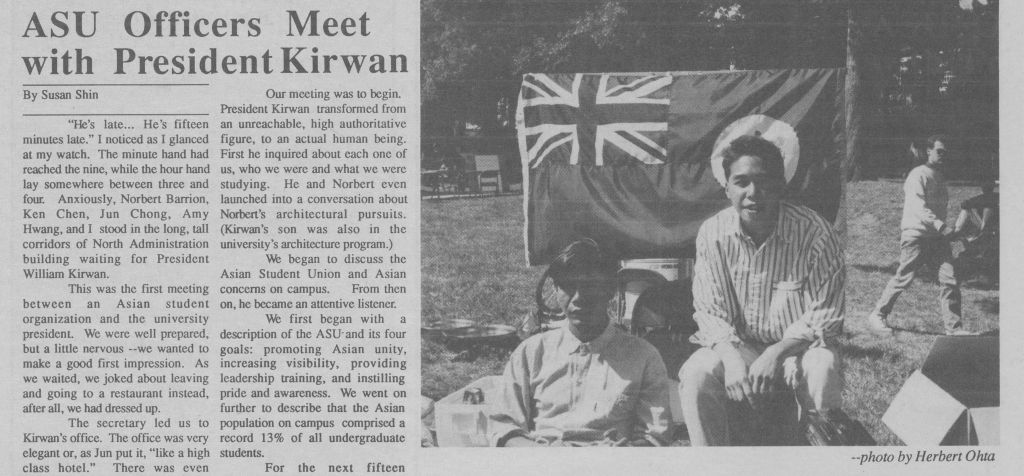

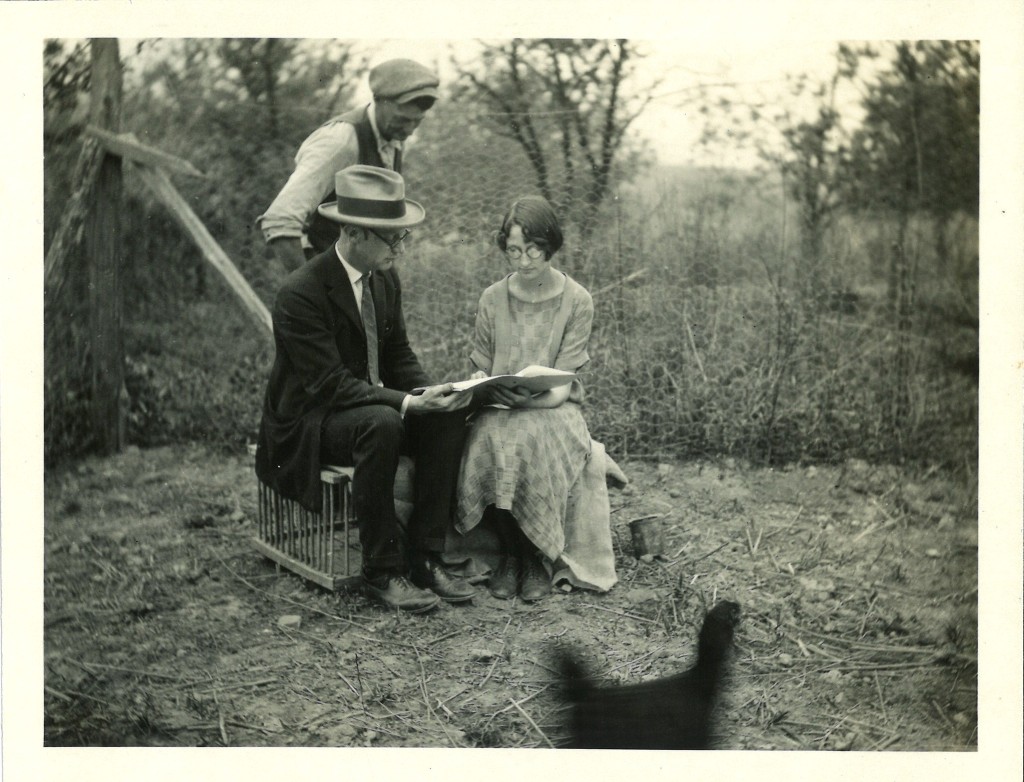

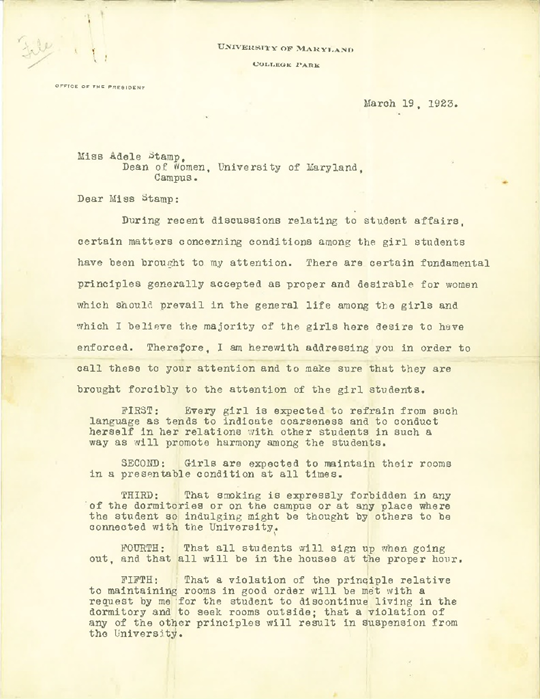

Testudo was chosen as the school mascot by the class of 1933 and then-VP Harry Clifton “Curley” Byrd, who didn’t seem to care whether the terrapin sent to him was male or female– he just wanted “the biggest one” to model for a statue. Below is a photo from the unveiling of the first Testudo statute, a ceremony attended by all the UMD big-names, like Senior class president Ralph Williams (far right), President Raymond Pearson (shaking hands with Williams), and Vice President Byrd (far left).

Testudo dedication ceremony, University of Maryland, June 2, 1933, Dept. of Intercollegiate Athletics Media Relations records, Box 23, folder “Mascot Testudo”, accession 2003-91.

Interestingly, and right in line with the topic of this blog post, the woman between Byrd and Pearson had remained unidentified on all copies of this photo. Either whoever took this photo in 1933 or whoever gave this photo to University Archives didn’t think it was important to write down the name of this woman- who was clearly important enough to the event to be front and center of the photo- and for decades, she was nameless. It may not seem like a big deal, but without a name, we were unable to give her credit for being a part of this event; we were unable to know how she was even connected to this event. Who was she, why was she there? For a long time, these questions went unanswered because someone took it upon themselves to erase her.

Now, we may have an answer. There’s no way for us to know for sure, but she may be Eva Catherine Bixler, and she was likely there because she was a part of the Women’s Student Government Association, which worked with the senior class president and the Student Government Assoc. to make this project happen. This rabbithole I went down to identify this woman was ironically perfect, though I guess it should come as no surprise; people have been trying to erase (important) women from history for centuries, whether it be their names and identities entirely or their womanhood– humans and animals alike, apparently.

Eva Catherine Bixler, Reveille 1933.

The terrapin that modelled for the statue was- for reasons we can probably guess and talk about for ages- assumed to be male (ironically, probably because of her large size) and the persona of a male Testudo was born. “Testudinette”, the female counterpart to Testudo, also existed, largely in the 1950s and 60s, but through to the 80s. She appeared in yearbooks, newspapers, programs, etc. But Testudo– the original Testudo, now taxidermized and living in University Archives,– was always assumed to be male.

Sez Testudinette article, Alumni Magazine, March-April 1956, p.58, accession LH 1. M3M3 vol. 37, folio.

That is, until John Pease, professor emeritus of Sociology at UMD, began to look into Testudo around 2018. His archival research on the mascot came up with a lot of general information, but none about its gender. So, Pease contacted Jennifer Murrow, an Environmental Science & Technology professor about biological signs that may point towards female or male. Murrow cited the “higher dome of the terrapin’s upper shell, its larger head, and its small tail” as signs that suggest Testudo was female!1

Original Testudo, taxidermized, Memorabilia Collection no. 171, University Archives, University of Maryland, College Park

There’s much to be said about the assumption of maleness in the first place, and why exactly mascots are always male. There’s even more to be said about what effect that’s had on how we perceive aggressiveness and ferocity as a society and how we’ve gendered certain traits.

In an article from the Diamondback, Alexis Lothian, Women’s Studies professor at UMD, said that without acknowledging a difference between male or female, “what you end up with is the status quo… The assumption of Testudo’s maleness probably speaks to the default maleness that is in operation all over the university, within sports, within academics and within many, many contexts.”2

Even Pease’s teaching assistant, Devorah Stavisky, spoke of Testudo’s assumed maleness and how that’s led to a portrayal of “brute force in ad campaigns”, which then feeds into “the image of what men should look like… what this school should look like”3, what power looks like (and who it belongs to). Especially considering how the university “has historically treated Testudo as a masculine symbol for our power as a university.”4

Though Testudo’s femaleness is a fun fact you can pull out at parties, it also says a lot about gender, power, and aggression— something to be unpacked in another, longer blog post perhaps.

For more about Testudo, check out these blog posts!

Original Testudo, taxidermized, Memorabilia Collection no. 171, University Archives, University of Maryland, College Park

Works Cited

1 Hunt, R. (October 14, 2018). It’s a girl! Researchers surprised to find the original Testudo may have been female. The Diamondback. https://dbknews.com/2018/10/14/umd-testudo-gender-mascot-terps-girl-female-research/

2 Hunt, R. (October 14, 2018). It’s a girl! Researchers surprised to find the original Testudo may have been female. The Diamondback. https://dbknews.com/2018/10/14/umd-testudo-gender-mascot-terps-girl-female-research/

3 DBK Admin. (December 31, 2018). We should celebrate Testudo’s female identity. The Diamondback. https://dbknews.com/0999/12/31/arc-cotudgxw45hu3ap5ixslqs7sh4/

4 DBK Admin. (December 31, 2018). We should celebrate Testudo’s female identity. The Diamondback. https://dbknews.com/0999/12/31/arc-cotudgxw45hu3ap5ixslqs7sh4/

Eleena Ghosh is a graduate student assistant in University Archives, pursuing a Master’s of Library and Information Sciences and a Museum Scholarship and Material Culture Certificate. She is interested in museum studies, creating more inclusive archival records and spaces, anthropology, and figuring out how to combine all of her different interests.