As we are sure it is for all of you, COVID-19 (commonly known as Coronavirus) is heavy on the minds of all of us at University Archives. This global health crisis has impacted the lives of the University of Maryland community in so many ways, both large and small. In light of this, the University of Maryland Libraries Special Collections and University Archives is launching the “Shell-tering in Place: Terp Stories of COVID-19” project. The goal of this project is to compile the stories of the UMD community’s experiences during the pandemic. We invite all members of the University community to contribute to the collection as we strive to record the ways our lives have been impacted by this historic moment.

As we arranged this collecting project, we also took time to reflect on the current global health crisis from an archival perspective. We reflected on the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic and how it impacted the University of Maryland campus community (then called Maryland State College). We hoped that seeing how the Spanish Flu was reflected in our archive might inform our understanding of how the COVID-19 pandemic may be remembered. What resulted was an observation on the ways archival collections might obscure the past and the ways we can contextualize archival materials to shed light on the past.

The Origins of the Spanish Flu:

In March 1918, soldiers at an Army base in Kansas fell ill with flu-like symptoms. What began as traditional flu symptoms of headache, fever, and nausea rapidly developed into severe pneumonia for these soldiers. Their ailment? The Spanish Flu: an avian flu that caused a pandemic in 1918. Within one week of the infections in Kansas, the number of cases had quintupled and the illness rapidly spread across the globe as soldiers traveled to Europe to fight in World War I. The 1918 flu pandemic unfolded in three waves of illness: the first in spring 1918, followed by a second wave in September 1918, and a third in January 1919. Historians estimate that approximately 500 million people contracted the virus, resulting in 50 million deaths worldwide. The Spanish Flu remains one of the largest pandemics in world history.

Gaps in the Record: Spanish Flu and Maryland State College

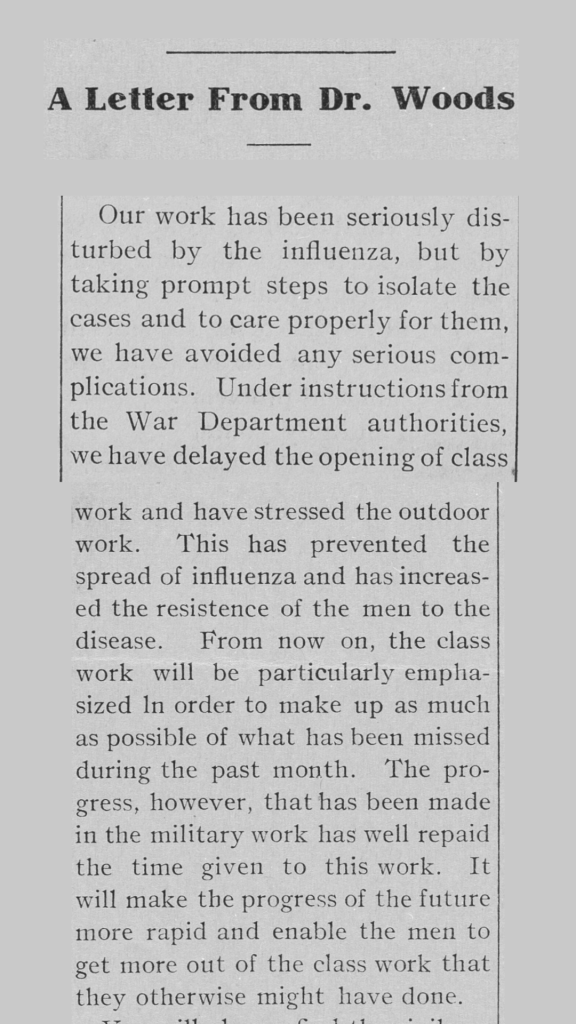

The first place we searched for information about the effect of the Spanish Flu on campus was the 1919 yearbook. Given that the influenza did not really take effect until April 1918, we knew that it would mostly appear in the yearbook of the following year. However, we were surprised to find no mention of the pandemic. Even in the sections that served as a reflection on the school year, there was no mention at all of the disease. Knowing that the disease had a widespread effect, we found it unlikely that no one on campus had contracted the flu, so we turned to the student newspaper, the Maryland State Weekly. From this, we discovered a relatively small number of mentions of the Spanish Flu or influenza. The most significant mention was in a published letter by the President of Maryland State College, Dr. Albert F. Woods, who wrote one short paragraph addressing the influenza:

We learned that the administration put classroom instruction on hold for the month of October and students mostly did outdoor coursework, which made sense since we were known as an agricultural school. According to Woods, this measure helped prevent the spread of the illness but other than this short paragraph, we found no other mentions of how the University dealt with the pandemic.

A handful of other mentions of the influenza in the paper seems to have fallen into one of two categories. The first is community updates. There are a smattering of short blurbs across issues of the Maryland State Weekly where they note the illness, recovery, or in a few cases, the passing of Maryland State College community members. From these, it is clear that the campus was significantly affected. Many members of the professoriate seem to have suffered from the flu at one point or another, and one esteemed faculty member, Professor E. F. Stoddard, died as a result of it.

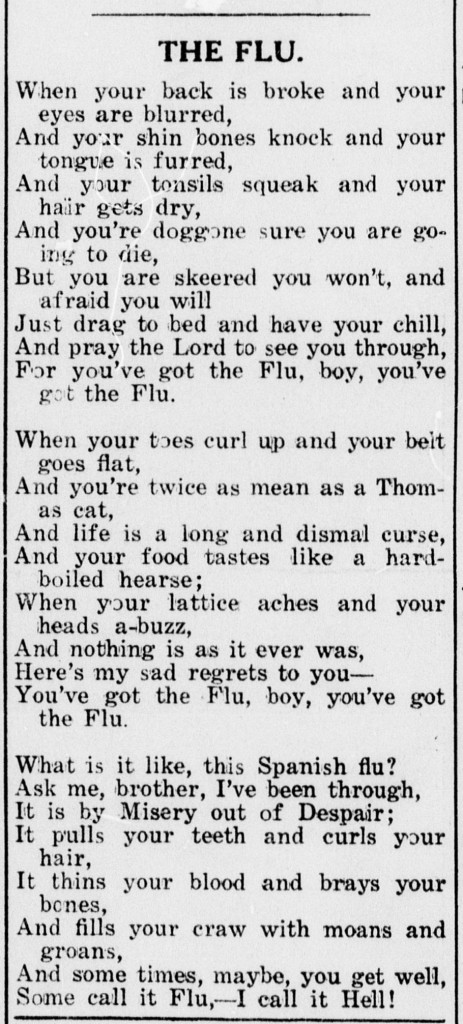

In contrast to these somber accounts, the second type of mentions seem to be more humorous. We found two poems in the student submitted sections that seemed to make light of the effects of the flu. There was also a reference to the flu in an article about the new dining hall that read:

“How can the old mess hall, in which there was no space, where the students had to crowd together like packed sardines; and where the danger of worse diseases than the Spanish Influenza was imminent, be compared with our new and spacious ‘Hotel’?”

Maryland State Weekly, 11/6/1918

We connected this sort of reference to the lighthearted responses to we are seeing across Instagram, Twitter, and other social media platforms right now. As people seek to alleviate the stress they are feeling, some are turning to humor in funny memes, tweets, and TikTok videos. In contrast to the huge amount of humorous quarantine related content saturating the internet right now, it was surprising to us that there were only three joking mentions of the Spanish Flu in the Maryland State Weekly.

Asking the Right Questions:

As you can see, the 1918 pandemic has a relatively small presence in our archival collections compared to the magnitude of the event worldwide. However, this seeming lack of sources has the potential to reveal a great deal about the pandemic and its impact on the Maryland State College campus. Historians employ the practice of reading sources “against the grain,” examining limitations, silences, and power dynamics in their sources alongside the information those sources actually contain. Why does our archive contain limited sources on this topic? And why did the College, the students, and the faculty hardly write about the personal impact of the flu, preventative measures, and its global spread? The lack of source material at University Archives relating to the 1918 flu prompts us to ask these questions and place our sources within a broader historical context to help us understand what may have actually been going on.

A lack of a response to a large historical event is a response. By placing our University specific sources within the larger historical context of 1918 and asking the right questions, we are able to gain a clearer understanding of what may have been happening on campus.

A key factor to consider when studying the Spanish Flu pandemic, is the U.S. involvement in World War I. The U.S. entered the global conflict in April 1917 and by June 1917, Congress had passed the Espionage Act which, among other restrictions, allowed censorship of the press. The government censored the information disseminated by large news agencies, and local journalists self-censored in fear of government sanctions. By government decree, the news was not allowed to reflect negatively on the military or hamper the war effort in any way. What does this have to do with Spanish Flu? Well, the very naming of the Spanish Flu was the result of WWI-related censorship of the press. Although historians now present evidence that the virus originated in Kansas, Spain was the first country to report infections in its newspapers. A neutral party during WWI, Spain did not censor its press while the U.S., Britain, Germany, and other warring nations prohibited the spread of news related to infected soldiers. With this information in hand, we can bring new perspective to the Maryland State Weekly’s mentions of the influenza outbreak. Rather than statistics, we find personal notices of illness. Instead of reports of the spread there is lighthearted poetry. What impact did the WWI culture of censorship have on the local campus press? Were mentions of the flu purposefully left out of print?

Asking specific questions about the historical context of WWI and censorship helps us understand the limitations of newspapers as sources during the pandemic. However, censorship does not explain other gaps in our archival record. The archive has almost no photographs, scrapbooks, or other papers describing the impact of the Spanish Flu on campus. Was the massive death toll too difficult to talk about in the wake of the pandemic? Were people embarrassed by the way they treated other people during the outbreak? Was the disease poorly understood and therefore not discussed on campus? These are all questions that beg greater exploration by researchers using our collections.

We also can question what materials made it to preservation in University Archives, examining gaps and silences in the collection of historical records. While individuals at the University of Maryland informally collected records pertaining to the history of the University, University Archives was not professionalized and did not hire an archivist until the early 1970s, over fifty years after the 1918 pandemic had subsided. Most of the earliest records on campus burned in a 1912 fire, and from 1912 until the 1940s materials related to the history of the University were not given collecting priority by the libraries. Collecting priorities shift over time, and it becomes difficult to collect items fifty years after events have passed. According to archival theorist Michel-Rolph Trouillot, silences are written into history at the moment of source creation, when the archives are created, and when researchers select which sources to use. Individuals chose what to record in 1918 about the flu, archivists chose what was important to collect regarding the flu, and researchers will choose what is important to highlight from our collections. All of these factors combine to limit what the archive tells us about the 1918 pandemic.

All of these factors are important to understanding our current situation and the role of archives in remembering the past. The sources highlighted here appear in marked contrast to the reaction now, where the University’s measures to keep staff and students safe are frequently updated and reported by many. The Diamondback has ongoing coverage of news related to COVID-19 and the topic is inescapable in any news source as it has impacted so much of our lives. While understanding the past does not prevent future disasters, there are important lessons we can learn today from studying and comparing responses to the COVID-19 pandemic and the 1918 pandemic. How will future researchers look back at the University of Maryland’s response to COVID-19? How can we account for differences and similarities in the way the campus responds to pandemics in very different historical moments? Are the silly flu poems of 1918 showing a similar response to the darkly funny memes and tweets of today? How have silences already worked their way into the ways we report on and preserve people’s experiences of COVID-19? And how can we work to eliminate these silences in our reporting, collecting, and writing?

Archives contain important tools and sources for understanding the past, but researching in our collections often requires a critical eye and a larger understanding of context. Archival research requires asking the right questions and reading between the gaps and silences in the historical record to gain a greater understanding of the past. At University Archives, we envision an inclusive and diverse collection that paints a broad view of the experiences of the University of Maryland community, including community experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.We invite members of the community to visit the collections landing page to read more about contributing to the COVID-19 collection. We hope to hear your stories soon!

Further Reading

Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History. New York: Penguin Books, 2004.

Benjamin, Walter. “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” 1942.

Billings, Molly. “The Influenza Pandemic of 1918.” Human Virology at Stanford University. February 2005. https://virus.stanford.edu/uda/.

“The Deadly Virus: The Influenza Epidemic of 1918.” National Archives and Records Administration. https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/influenza-epidemic/records-list.html.

Stoykovich, Eric. “History of Special Collections and University Archives.” University of Maryland Libraries. January 2019. https://www.lib.umd.edu/special/about/history-of-scua.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press, 1995.

“1918 Pandemic (H1N1 Virus).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. March 20, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html.