This is the second of two posts exploring the history of integration at the University of Maryland. Read part one here.

The lawsuit resulting in Donald Murray’s admission to the University of Maryland School of Law in 1936 was an important step in breaking down Jim Crow policies of “separate but equal” facilities for higher education here in Maryland. A decade later, Murray and Thurgood Marshall would work together to put an end to segregation at the University of Maryland.

In the 1940s, the university employed two strategies to maintain its segregationist policies while trying to appease the African-American community. One was to provide black applicants to the university with scholarships to out-of-state institutions that had similar programs. The second was to create separate programs for black students that took place at sites like high schools in Baltimore or on the campus of the Maryland State Teachers College at Bowie. The scholarship approach lent fuel to a new round of lawsuits, while the second approach led to our next round of trailblazers.

In 1948, three teachers- Rose Shockley Wiseman, Myrtle Holmes Wake, and John Francis Davis – began graduate studies in the College of Education under the guidance of Dr. Daniel Prescott, founder of the Institute for Child Study. The three took their classes together whenever they weren’t teaching and were taught by professors from the College Park campus, who traveled to the Bowie campus every day. On June 9, 1951, Wiseman, Wake and Davis received their diplomas in person at the commencement ceremony at College Park, becoming the first African-Americans to do so.

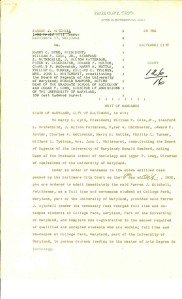

The court issued Writs of Mandamus in 1950 for McCready and Mitchell, while Whittle was eventually admitted without court intervention in 1951. Mitchell graduated in 1952 and McCready in 1953, while Whittle left College Park after his first year. Parren Mitchell went on to become Maryland’s first black member of Congress, serving Baltimore’s 7th District from 1971-1987.

The 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown vs. Board of Education removed any legal basis for segregation at the University of Maryland. The road to Brown was a long one and was made possible in part by the sacrifices and victories of our trailblazers- Harry S. Cummings, Donald G. Murray, Rose Shockley Wiseman, Myrtle Holmes Wake, John Francis Davis, Esther McCready, Parren J. Mitchell and Hiram Whittle. Their names will live forever in the history of the University of Maryland.

Learn more about Parren Mitchell: Part 1, Part 2

Sources:

University of Maryland (College Park, Md.). President’s Office records. Folders titled “Negro Education”.